Sixty three years ago, today, JFK’s head exploded out of the back of his Lincoln Continental as it drove through Dealey Plaza. A certain American hopefulness went with it. I’m not in the business of Kennedy-fetishism; the shimmering vision of Camelot that was pure and clean and true. Nevertheless, the man had 1) begun talks of pulling troops out of Vietnam, 2) opened back channels to negotiate peace with the Soviet Union, and most importantly, 3) had fired Allen Dulles in 1961 after the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion. These three instances placed Kennedy in opposition to the Cold War, and by extension, to the CIA itself. Now, like I said, I don’t think it’s like that sci-fi utopia meme of “the world if X didn’t happen,” but when JFK was killed, as Don DeLillo puts it, “the process of unraveling could safely begin.” The CIA had flexed their muscles as hard as it could, and there was no going back. It was impossible to know the full extent of it then, but the Cold War created the industry of the abstract and eternal “war.” It brought us big hits like the War on Drugs and the War on Terror. I’d hope anyone that is reading this will surely know, these are all just veils to justify the ruling class doing whatever they want all the time forever.

I am not going to plot out all the different lines and theories of who really fired the shot, from where, with what kind of gun, yada yada yada. There is enough of that already. I don’t really care who fired the shot and what their specific line-of-sight looked like (it was from the grassy knoll though). All that I’m interested in is that it was the CIA. Oswald was certainly involved, but he also was certainly not alone. Even more importantly, I want to look at the symbolic historical moment of trauma that occurred on November 22nd, 1963 in Dallas.

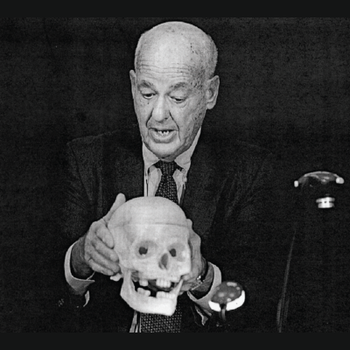

The details surrounding the assisnation have been written into the Warren Commission Report. DeLillo described this 26-volume long document as “the Joycean Book of America,” this is what Joyce would have done to follow up Finnegan’s Wake, “if he had moved to Iowa City and lived to be a hundred.” It is with this in mind, that I am drawn to fiction as a route to talk about the JFK assasnation. The “truth” of the matter has been obscured, erased, and deleted in the six decades since, so why not turn to the novel to try to situate ourselves within this madness, specifically, Don DeLillo’s Libra, a semi-fictional account of Lee Harvey Oswald’s life and his attempts to become a part of History. DeLillo’s novel follows three concentric layers of historical representation. First, we see Oswald’s life as it slowly intersects and is consumed by the CIA plot that was “written” for him by the agents. Then, we see Nicholas Branch, the fictional record-keeper in the 1980s trying to assemble a cohesive record of events. And finally, we have DeLillo’s fictional account of the historical events via his novel. As we move from the event itself (as it really occurred in reality), through each of these layers of representation, everything gets less and less stable and clear. This brings us back to DeLillo’s joke about the Warren Commission Report being a cryptic modernist novel. Sure, it is the official “historical” record, but it is no more clear and grounded in reality than any of these other “records.” Hell, the Commision consisted of people like John McCloy, a key figure in the Japanese internment and President of the World Bank, and Allen fucking Dulles, the former head of the CIA that JFK forced to resign. Surely, this crew of ghouls is interested in Truth and Justice for the American people!

Tracing Oswald’s path leading up to that day at Dealey Plaza would show dozens of strings, intersecting and looping around each other before all being crammed into that room on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository building. DeLillo’s Oswald is a man who feels shut out from “the world in general,” from History. His early interest in communism as a means to this end (joining a force in the motion of History) is slowly revealed to be little more than a means to this end. It isn’t about Marxism or the real material struggle of some attempt to build socialism, but the exalted ideal that is represented by the Soviet Union. Like any ideal that has been placed in the most high, real exposure to it will inevitably fail to meet the expectations. We saw this in Oswald’s realization that the “USSR is only great in literature.” Only in the neatly written and textualized version of this idea could Oswald find a sense of purpose. Nevertheless, he continues trying (and failing), and each time DeLillo is unraveling his own stability of identity. It is the seeking, the yearning, the potential that seems to hold him together. As we get closer to November ‘63, the “text” of Oswald in the historical record begins to disintegrate. Again, as Oswald begins to fragment, it is Win Everett (whose description lines up with the real life of CIA agent Birch O’Neil) who constructs him; “putting together a man with scissors and tape.”

In the months leading up to November, there were a number of Oswald sightings with contrasting records of where Oswald would have been at the time. The most ridiculous of which involved Oswald’s alleged trip to Mexico city. I think it is very possible that Oswald did actually go to Mexico to visit the Soviet Embassy and the Cuban consulate, but the photo on record of “Oswald” leaving the Cuban consulate is truly outrageous. The fact that it was ever suggested that the photographed man was Oswald shows the contempt these people have for us.

With Oswald becoming even less of a unified and identifiable subject, DeLillo uses these disparate strings of identity to define Oswald’s characterization by its very fragility, as someone who grasps to any potential source of stable and grand purpose. This is the symbolic representation of the typical American’s relationship to Kennedy as an icon, grasping to this exalted figure for the stability it could potentially provide. Kennedy occupied this paradoxical space of being a promise of change, of a new future, while possessing all of the idealized comfort of the status quo. The romanticized image of Camelot showed people what they could hope for in their own lives, something that could only be achieved through Kennedy’s providence. DeLillo writes of Kennedy's arrival in Dallas as a means of turning the masses of figures into a definite gathering, as if seeing Kennedy in the flesh suddenly provided these isolated individuals with a sense of social cohesion. As the third and final shot was fired, however, this sense of a cohesive social identity, tied together by Kennedy’s glimmer, was pulverized into a red mist. As DeLillo puts it, this shot “sent stuff just everywhere.” Not just Kennedy’s organic matter, but the hope “American” might have meant something; that maybe we too could achieve all our dreams without any risk of failure; and on some unconscious level: that maybe our collectivity could resist the alienating effects of capitalism’s conquest of the world.

This symbolic moment of collective historical trauma was one of the few origin points in the history of the America we are currently surrounded by. Dulles, Bush, and all the rest of the ghouls were free-rolled from then onward, and history shows how they took advantage of that. In Libra, as Oswald fled the scene, his ability to identify himself became externalized. He saw himself through the lens of the cops that might be looking for him, as a description of a suspect. “All the clarity was gone. There was a nervous static in the air.” The radio, which served as a beacon of formalized meaning through the novel, had devolved into distorted fragments of language. For Americans, the decades following brought a similar externalization of identity and a breakdown of stable understandings of “truth”. In place of a stable identity through which we could relate to the world, we were told to buy shit. This was how we could beat those commies! This is how we could exercise what makes us American! The abstract ideal of “freedom” could now be fully contained by our freedom to purchase things on the market and consume them how we liked. Not only was it the threat of nuclear destruction of the Soviet Union, but the divine power of American consumerism that “won” the Cold War! All the while, it provided a new level of obfuscation, concealing the dark underside of mass consumerism. (see DeLillo’s Underworld).

The Cold War eventually came to an end, but the War on Drugs was already established to take the mantle. They started overlapping and intertwining via Iran-Contra and it was solidified in law with Clinton’s mandatory minimums. Then came 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq, establishing the War on Terror. The point is: there will always be another “communist” or “superpredator” or “Islamic extremist.” These abstract, and therefore unlimited, existential threats are the key to capital’s maintenance and global expansion. On November 22nd, 1963, they showed us real clearly what would happen to anyone who questioned this route.